Google’s Project Suncatcher and Why Space May Become AI’s New Home

AI is rapidly advancing and proliferating; from simple text-based queries popularised by the launch of ChatGPT in 2022, to AI-generated videos now almost indistinguishable from real life, save for the faint ‘Sora AI’ watermark. The emergence of AI-enabled robotics adds yet another layer of demand, with machines requiring continuous connectivity to data centres to function intelligently.

However, AI’s growth comes with a substantial burden on power systems. A December 2024 report by the US Department of Energy predicts that AI data centres will consume up to 12% of the country’s electricity by 2028, compared with 4% in 2023. As a result, building, running, and leasing data centres is becoming increasingly expensive: electricity demand is rising, pushing prices higher, while larger facilities require greater power input, forcing utilities to upgrade grids: costs that ultimately feed through to end-users. These pressures are expected to continue as AI adoption accelerates.

At the same time, the environmental impact of data centres is escalating. Larger facilities require more land, power and cooling, increasing their footprint and intensifying their effect on surrounding areas. Northern Virginia - widely regarded as the data centre capital of the world - illustrates this clearly, with residents and advocacy groups frequently raising concerns about noise and air pollution.

Current Data Centres in North Virginia

Source: VEDP

Source: VEDP

Without meaningful intervention, electricity usage in countries leading AI development, particularly the US and China, is likely to double over the next decade.

One radical intervention now being explored is building data centres in space. Google’s Project Suncatcher - announced last month - is the most comprehensive plan to date for launching data centre infrastructure beyond Earth. The project, outlined via a blog and research paper, sets out Google’s ambition to construct scalable Low Earth Orbit (LEO) data centres to power AI workloads on Earth.

Google plans to launch two prototype satellites equipped with its Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) in 2027 in partnership with Planet, a satellite imagery company, before expanding to a potential 81-satellite constellation in 2030. TPUs are custom chips developed by Google to power machine learning. According to the research, the constellation will deliver computational capacity comparable to terrestrial facilities. The satellites will use Free Space Optics (FSO), Dense Wavelength-Division Multiplexing (DWDM) and Spatial Multiplexing (SM) technologies to transfer data between one another.

Industry support is emerging. Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos have publicly expressed interest in the broader concept of space-based data centers and AI infrastructure in orbit, and both possess the influence, launch capability and capital to help drive it forward. Additional involvement from companies beyond Google will be essential to scale momentum and reduce cost barriers.

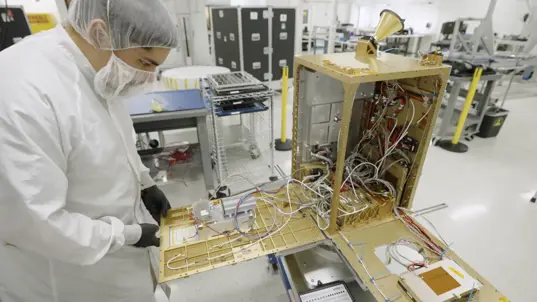

Progress is visible elsewhere too. Starcloud, a startup backed by NVIDIA and Y Combinator, launched a satellite in November 2025 containing an NVIDIA H100 GPU in a pilot test. Like Google, Starcloud aims to establish data centres in space; initially powered by NVIDIA hardware.

Source: Starcloud/NVIDIA

Advantages of Data Centres in Space

Space-based data centres address many of the issues associated with terrestrial facilities, particularly energy. In LEO, data centres can access near-constant solar energy, removing demand from national grids and reducing environmental impact relative to power usage. This renewable supply bypasses the need for utilities to invest in grid upgrades to meet rising demand.

Space also offers potential cooling advantages. Near-vacuum conditions could enable radiation-based cooling for TPUs used in AI services. While technically complex, Juniper Research believes this could provide significant long-term benefits, avoiding future regulations surrounding water usage and natural resource consumption.

Although launching satellites is costly, prices are expected to fall over the next decade. Google’s Suncatcher research suggests launch costs may drop below $200/kg by the mid-2030s. At this level, the amortised launch cost over spacecraft life could approximate terrestrial data centre energy expenses on a per-kW basis.

Challenges

Despite the progress, major obstacles remain. Space is an extreme operating environment. Radiation can damage key components, including processors and GPUs. Google reports testing its v6e Trillium TPU using a 67MeV proton beam to simulate ionising radiation, with results showing no failures attributable to the exposure. While promising, laboratory results cannot perfectly replicate fluctuating space conditions.

Physical risks also exist. Debris and micrometeorites travel at hypersonic speeds of around 17,500 miles per hour and can damage satellites. Unlike terrestrial data centres, repairs are complex, slow and costly; frequent failures could erode potential savings if repair missions become necessary.

Orbital congestion adds another challenge. SpaceX reported 144,000 manoeuvres from December 2024 to May 2025 - around 791 per day - to avoid debris. Google notes that its satellites will use a machine learning-based flight control model to maintain proximity while avoiding collisions, but provides little detail on redundancy or real-time management, raising questions about long-term reliability.

Technical complexity also arises when deploying FSO, DWDM and SM simultaneously. These systems can interfere due to atmospheric turbulence, causing beam wandering or distortion. Google acknowledges this and suggests aligning satellites closely to minimise divergence, but implementation remains demanding.

Conclusion

For Google to succeed in this endeavour, it must implement an autonomous collision-avoidance system similar to Starlink’s, powered by onboard AI. As LEO becomes increasingly congested, Juniper Research expects it to become more difficult for enterprises to safeguard constellations; making advanced avoidance systems essential. Redundant provisioning may not be sufficient if physical damage renders satellites inoperative or disrupts network integrity.

For space-based data centres to reach their full potential, Juniper Research recommends collaborative effort among vendors such as SpaceX, Google, NVIDIA and Amazon; pooling capabilities to design technology that enables consistent and reliable operation in space.

Ardit works within the Telecoms & Connectivity team; providing insights and strategic recommendations on current and future markets within the telecoms industry. His primary area of focus is on operator and CSP strategies. He previously worked at GlobalData for four years where he covered the technology and telecommunications industries, and prior to that, worked at Gartner for two years.

Latest research, whitepapers & press releases

-

ReportMarch 2026Fintech & PaymentsCross-border Payments Market: 2026-2030

ReportMarch 2026Fintech & PaymentsCross-border Payments Market: 2026-2030Our Cross-border Payments research suite provides a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the evolving cross-border payments landscape; enabling stakeholders such as businesses, financial institutions, payment service providers, card networks, regulators, and technology infrastructure providers to understand future growth, key trends, and the competitive environment.

VIEW -

ReportFebruary 2026Telecoms & ConnectivityMobile Messaging Market: 2026-2030

ReportFebruary 2026Telecoms & ConnectivityMobile Messaging Market: 2026-2030Juniper Research’s Mobile Messaging research suite provides mobile messaging vendors, mobile network operators, and enterprises with intelligence on how to capitalise on changing market dynamics within the mobile messaging market.

VIEW -

ReportFebruary 2026Fintech & PaymentsKYC/KYB Systems Market: 2026-2030

ReportFebruary 2026Fintech & PaymentsKYC/KYB Systems Market: 2026-2030Our KYC/KYB Systems research suite provides a detailed and insightful analysis of an evolving market; enabling stakeholders such as financial institutions, eCommerce platforms, regulatory agencies and technology vendors to understand future growth, key trends and the competitive environment.

VIEW -

ReportFebruary 2026Telecoms & ConnectivityRCS for Business Market: 2026-2030

ReportFebruary 2026Telecoms & ConnectivityRCS for Business Market: 2026-2030Our comprehensive RCS for Business research suite provides an in‑depth evaluation of a market poised for rapid expansion over the next five years. It equips stakeholders with clear insight into the most significant opportunities emerging over the next two years.

VIEW -

ReportFebruary 2026Fintech & PaymentsMobile Money in Emerging Markets: 2026-2030

ReportFebruary 2026Fintech & PaymentsMobile Money in Emerging Markets: 2026-2030Our Mobile Money in Emerging Markets research report provides detailed evaluation and analysis of the ways in which the mobile financial services space is evolving and developing.

VIEW -

ReportJanuary 2026IoT & Emerging TechnologyPost-quantum Cryptography Market: 2026-2035

ReportJanuary 2026IoT & Emerging TechnologyPost-quantum Cryptography Market: 2026-2035Juniper Research’s Post-quantum Cryptography (PQC) research suite provides a comprehensive and insightful analysis of this market; enabling stakeholders, including PQC-enabled platform providers, specialists, cybersecurity consultancies, and many others, to understand future growth, key trends, and the competitive environment.

VIEW

-

WhitepaperMarch 2026Telecoms & Connectivity

WhitepaperMarch 2026Telecoms & ConnectivityMWC 2026: What's Next for Mobile?

Our latest whitepaper distils the most important announcements from MWC Barcelona 2026 and examines what they mean for the telecoms market over the year ahead. From network APIs and 5G monetisation to AI-RAN, direct-to-cell connectivity, and 5G-Advanced, it explains where the biggest opportunities — and challenges — will emerge next.

VIEW -

WhitepaperMarch 2026Fintech & Payments

WhitepaperMarch 2026Fintech & PaymentsThe Transformation of Cross-border Payment Infrastructure

Our complimentary whitepaper, The Transformation of Cross-border Payment Infrastructure, examines the state of the cross-border payments market; explaining the role of key actors in transforming the cross-border payment experience, as well as the current landscape and recent developments within the cross-border payments industry.

VIEW -

WhitepaperFebruary 2026Telecoms & Connectivity

WhitepaperFebruary 2026Telecoms & ConnectivityHow Social Media Will Disrupt Mobile Messaging Channels in 2026

Our complimentary whitepaper, How Social Media Will Disrupt Mobile Messaging Channels in 2026, explores the challenges and opportunities for operators and enterprises as social media traffic continues to increase.

VIEW -

WhitepaperFebruary 2026Telecoms & Connectivity

WhitepaperFebruary 2026Telecoms & ConnectivityProtecting Users from Scam Ads: A Call for Social Media Platform Accountability

In this new whitepaper commissioned by Revolut, Juniper Research examines how scam advertising has become embedded across major social media platforms, quantifies the scale of user exposure and financial harm, and explains why current detection and enforcement measures are failing to keep pace.

VIEW -

WhitepaperFebruary 2026Fintech & Payments

WhitepaperFebruary 2026Fintech & PaymentsKnow Your Agents (KYA): The Next Frontier in KYC/KYB Systems

Our complimentary whitepaper, Know Your Agents (KYA): The Next Frontier in KYC/KYB Systems, examines the state of the KYC/KYB systems market; considering the impact of regulatory development, emerging risk factors such as identity enabled fraud, and how identity and business verification is evolving beyond traditional customer and merchant onboarding toward agent-level governance.

VIEW -

WhitepaperFebruary 2026Telecoms & Connectivity

WhitepaperFebruary 2026Telecoms & Connectivity3 Key Strategies for Capitalising on RCS Growth in 2026

Our complimentary whitepaper, 3 Key Strategies for Capitalising on RCS Growth in 2026, explores key trends shaping the RCS for Business market and outlines how mobile operators and platforms can accelerate adoption and maximise revenue over the next 12 months.

VIEW

-

Fintech & Payments

Sophisticated Microfinance Services Spend to Surpass $22 billion By 2030, as Mobile Money Services in Emerging Markets Mature

March 2026 -

Fintech & Payments

Top Three Global Leaders in Cross-border Payment Infrastructure Revealed

March 2026 -

Telecoms & Connectivity

MVNO Subscriber Revenue to Exceed $50 Billion Globally in 2030

March 2026 -

Fintech & Payments

QUBE Events is excited to bring back the 24th NextGen Payments & RegTech Forum - Switzerland

February 2026 -

Telecoms & Connectivity

OTT Messaging Apps to Exceed 5 Billion Users Globally by 2028; Driving Shift in Enterprise Communication Strategies

February 2026 -

Fintech & Payments

Calling All Fintech & Payment Innovators: Future Digital Awards Now Open for 2026

February 2026